26 Jul How is Rosé Wine Made?

Thanks to our very brief history of rosé, we know that rosé has been made around the world for quite some time now. But how exactly is it made?

Traditionally there are three ways to make rosé. Depending on who you talk to, you’ll get a different answer as to which is the “best” way to make it. Essentially, winemaking doesn’t really have any hard-and-fast rule to what is “correct.” There are rough guides of how to do things, but part of the beauty of winemaking is that it’s a blend of art and science. Everyone has their interpretations, and that’s okay. As the saying goes, “ask four different winemakers a question, you’ll get 16 different answers.”

For the most part, rosé is made in the following ways…

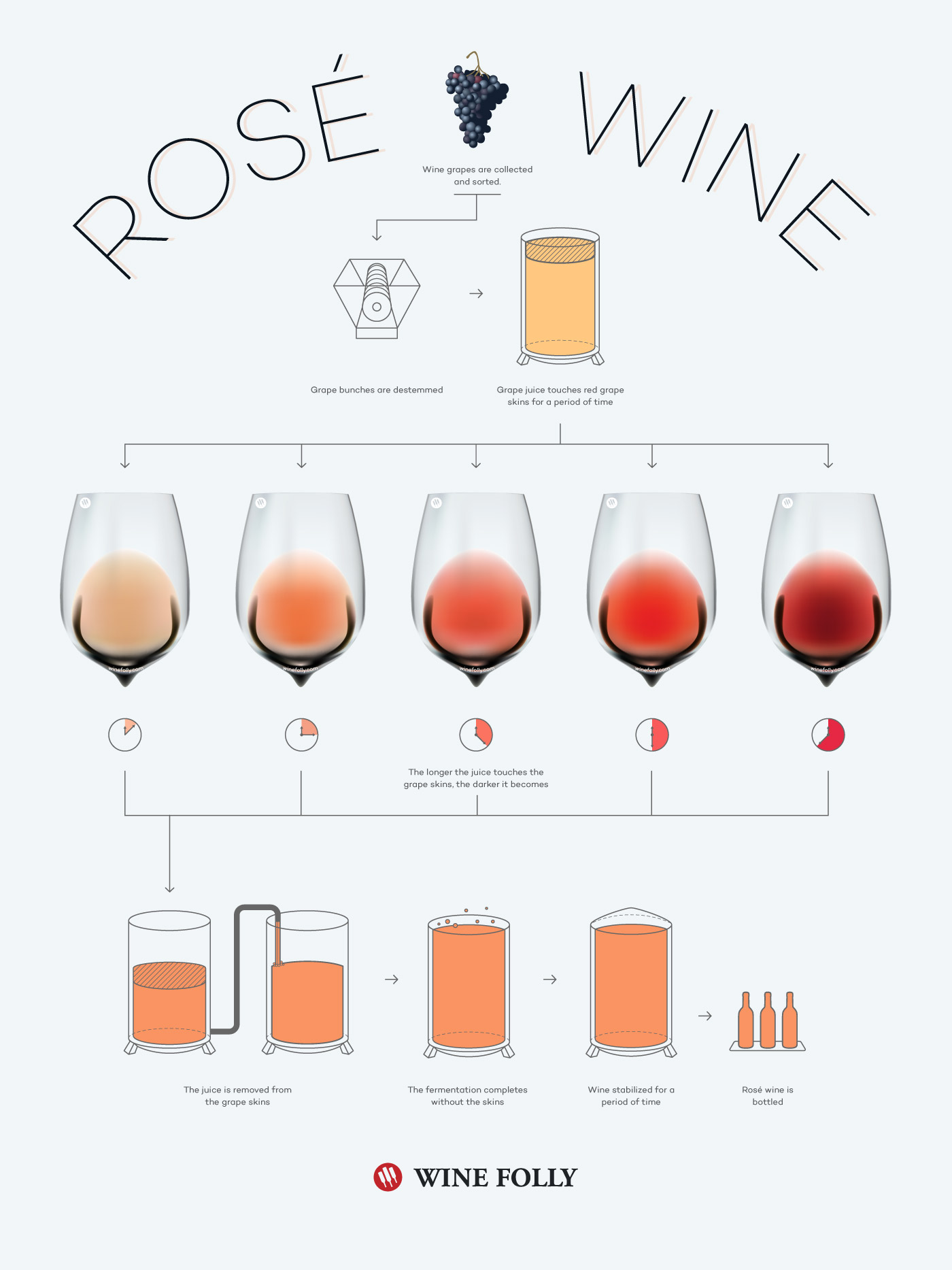

courtesy of Wine Folly

courtesy of Wine Folly

Direct Press Method

Making rosé in the direct press method is often referred to as “intentional,” or “true” rosé. A winemaker harvests fully-ripe red wine grapes, takes them to the winery, and squeezes out the juice from the grapes.

Fun fact, the juice inside of grapes is a clear liquid. That goes for both red and white grapes. Grape skins contain pigments which give the grape its color. As the juice comes out of each grape it comes into contact with the outside skin of the grape. The juice then is dyed by the pigment in the grape’s skin. Since the juice to skin contact is very quick, the juice only extracts a small amount of the pigment rendering the juice now a lighter hue of pink.

Fun fact, the juice inside of grapes is a clear liquid.

Many winemakers profess that direct press rosé is the purest form. It preserves all of the light red fruit, citrus, melon, and floral aromatics of the wine. Producers such as Domaine Tempier of Bandol in the South of France only make rosé in the direct press method. Wine critic Robert Parker once noted Tempier’s rosé as, “the greatest rosé in the world.” Like Tempier, the majority of rosé produced in the South of France, particularly in Provence, is made in the direct press method. It renders the classic “salmon pink” color often desired around the world. Is it the best method? Who can say? At Joseph Jewell, we make our rosé of pinot noir in a direct press method. Maybe that’s why it’s so good!

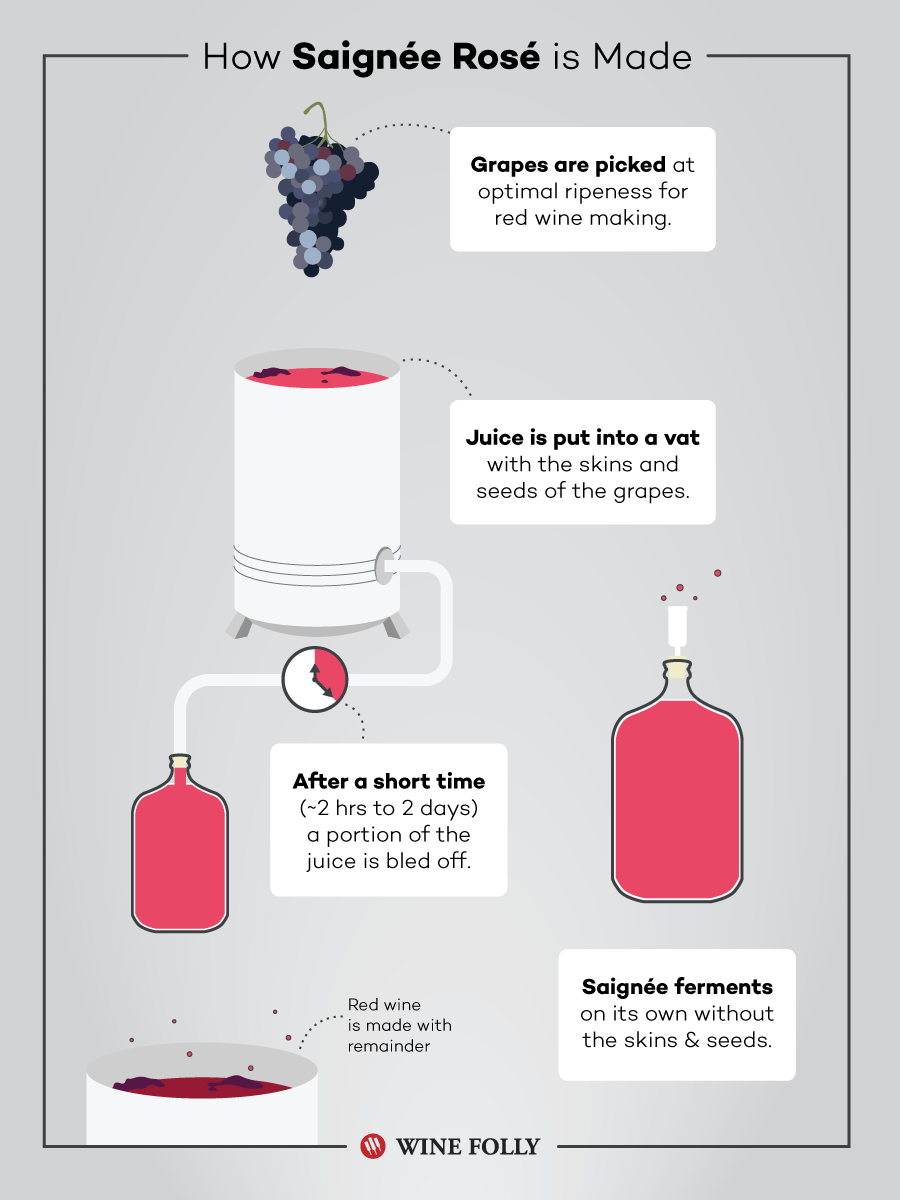

Saignée or Bled Method

Saignée (sohn-yay) means “to bleed,” and is one of the most common ways to make rosé. Like the direct press method, a winemaker starts with ripe red wine grapes, but in this case the grapes are harvested for making a red wine.

When the grapes are brought to the winery they are put into a fermentation vessel (stainless steel tank, large wood barrels, concrete eggs, etc.) and left in there for a time frame ranging from 2 hours to several days. During this time, the weight of the grapes on top of each other cause the grapes to break open, allowing the juice to come out. Same as with what happens when utilizing the direct press method, the clear grape juice comes in contact with the pigments of the grape skins. Since the juice and grapes are together in a large vessel with no way of getting away from each other, the amount of pigment that the juice extracts from the skins is greater, causing the juice to turn a darker hue of pink. Once the desired time frame is up, the winemaker will “bleed,” or drain off a portion of the juice from the tank. A lovely shade of pink juice is now separated and able to ferment on its own without any more color extraction.

Saignée method rosés are often darker in color than direct press rosés and sometimes have more dark fruit notes of dark cherry, blackberry, blueberry, and herbal notes like eucalyptus or bay laurel. This method is very popular in Spain where they produce very dark red wines such as Tempranillo, Garnacha, Mencia, Bobal, and Trepat.

courtesy of Wine Folly

courtesy of Wine Folly

Blending Method

Similar to how the ancients diluted their still red wines with water to produce rosé, winemakers today also make rosé by blending multiple liquids. However, instead of diluting with water, they dilute with white wine.

Popular in the Champagne region of France to make rosé Champagne, winemakers will produce a white wine from the grape of their choice, often times Chardonnay, and add a small percentage of still red wine made of either Pinot Noir or the more red and tannic, Pinot Meunier.

From an aromatic and flavor standpoint, blending white wine with a red wine enables more flavors to come out.

Why would a winemaker choose this method over either of the above? When it comes to producing rosé Champagne, or sparkling rosé in general, wine grapes such as Chardonnay have a higher amount of lipids. These lipids help to create smaller bubbles in the wine, known as the mousse, and retain a larger concentration of bubbles for a longer period of time so that the wine doesn’t go flat. From an aromatic and flavor standpoint, blending white wine with a red wine enables more flavors to come out. It’s like adding more than one spice to a dish. From the Chardonnay you get notes of apple, pear, and lemon, while the red wine brings in notes of red cherry, raspberry, strawberry, and more. In short, blending wines together creates more complexity than you would find if just using one type of grape.

For each way rosé can be made, there is a unique interpretation of the pink libation waiting to be enjoyed. This is what makes rosé as a wine so interesting and unique. There is a rosé for just about any food pairing, with the myriad of flavor profiles waiting to be experienced.